Bulgaria Supported Partially the EMU Stability Treaty

Ralitsa Kovacheva, January 31, 2012

Bulgarian National Assembly has given the government a mandate to negotiate on our participation in the new Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU)". This is an intergovernmental agreement agreed at the end of last year, previously known as 'fiscal compact', which got its current name after four revisions of the text. It provides for additional measures for strict budgetary discipline and closer coordination of economic policies of the eurozone countries. Last December the European Council agreed on the participation of countries outside the euro area that are willing to support the Treaty, fully or partially. Then Bulgaria, via Prime Minister Boyko Borissov, stated its willingness to participate, as well as most of the other EU countries.

Bulgarian National Assembly has given the government a mandate to negotiate on our participation in the new Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU)". This is an intergovernmental agreement agreed at the end of last year, previously known as 'fiscal compact', which got its current name after four revisions of the text. It provides for additional measures for strict budgetary discipline and closer coordination of economic policies of the eurozone countries. Last December the European Council agreed on the participation of countries outside the euro area that are willing to support the Treaty, fully or partially. Then Bulgaria, via Prime Minister Boyko Borissov, stated its willingness to participate, as well as most of the other EU countries.

As can be seen in the decision of Parliament, adopted on Friday, 27 January, at this stage Bulgaria will support only Title ІІІ of the treaty, the so called Fiscal Compact, which provides measures for stricter budget discipline: inscribing a "golden rule" in the constitution to limit debt and deficit, introducing automatic correction mechanisms in case of deviation from budgetary targets and the possibility a Member State to be brought before the EU Court of Justice if not complying with its obligations under the Treaty. With regard to Title IV of the Treaty, which provides for closer coordination of economic policies, its provisions will apply to Bulgaria after the country joins the euro.

The Parliament's decision explicitly states that support to the Treaty must not lead to financial obligations for Bulgaria, as well as "commitment to harmonise its tax policy with the contracting parties." This was also highlighted in the statements of the representatives of the ruling party GERB [member of the EPP] – both MPs and ministers Simeon Djankov (of Finance) and Nickolay Mladenov (of Foreign Affairs). "The economic and fiscal coordination in the EU is the worst thing that can happen to Bulgaria," Martin Dimitrov, Co-chair of the Blue Coalition and leader of the Union of Democratic Forces (UDF), said. What does it mean, if we want to make pension reform to coordinate it with another 25 countries, the MP indignantly asked, answering himself: it means centralisation."If we do not oppose a centralised Europe, we will pay the bill tomorrow."

In fact, this Title IV, described as a great danger for Bulgaria by politicians and  economists, contains only general guidelines for coordination of policies "essential to the smooth functioning of the euro area." In the latest draft even the reference to the Euro Plus Pact (also joined by Bulgaria) has been removed, where tax coordination is mentioned. According to the statement of Finance Minister Simeon Djankov before the National Assembly, Bulgaria has explicitly requested no reference in the Treaty to the Euro Plus Pact to be made. The topic "Is Tax Harmonisation in the EU Dangerous" has provoked hot debates on this web site.

economists, contains only general guidelines for coordination of policies "essential to the smooth functioning of the euro area." In the latest draft even the reference to the Euro Plus Pact (also joined by Bulgaria) has been removed, where tax coordination is mentioned. According to the statement of Finance Minister Simeon Djankov before the National Assembly, Bulgaria has explicitly requested no reference in the Treaty to the Euro Plus Pact to be made. The topic "Is Tax Harmonisation in the EU Dangerous" has provoked hot debates on this web site.

The opposition, in the face of the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) and the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (MRF), launched the thesis that Bulgaria could only win if supporting the part of the Treaty devoted on coordination of economic policies. According to MP Aliosman Imamov (MRF), the main purpose of Bulgaria in terms of this Treaty should be to participate in the development of policies that promote economic development and enhance convergence at EU level.

"The question is what is our position after the call of Ms Merkel for more Europe. Balkan tricks are an extremely dangerous thing – we are joining some clauses, but not the fourth chapter. Why are we running away exactly from this chapter? They say - it would increase our taxes. We continue to play ideologemes, without taking an accurate account of what we want to achieve. [...] This treaty is the first step towards the formation of a common European economic policy. The question is what is the position of Bulgaria," socialist MP and former economy minister Rumen Ovcharov asked.

He added that "this treaty is related to direct financial commitments of Bulgaria from the moment of our entry into the eurozone." Perhaps Mr Ovcharov had in mind the link with the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the permanent rescue fund for the euro area. However, it is established with a separate agreement, which Bulgaria has to sign anyway, given that under its accession treaty the country is required to adopt the euro once it meets the criteria. And despite the confusion, which occurred in Bulgaria last spring and has still not been completely distracted, the ESM contributions have nothing to do with both the new stability treaty and the Euro Plus Pact. The text of the ESM Treaty has also been changed in relation to the Stability Treaty, as well as the need the fund to be activated earlier - in July 2012, and will be approved by the European Council on Monday, 30 January.

The general impression was that the members of the opposition parties BSP and the MRF were more prepared in terms of the text of the stability treaty and used more specific arguments, though at some points - in a quite manipulative manner. However, members of the majority relied as usual on political slogans and hollow phrases, leaving Foreign Minister Nickolay Mladenov to refute alone the opposition's criticism and to justify the government’s position.

Ivan Kostov, Co-chair of the Blue Coalition and leader of Democrats for Strong Bulgaria (DSB), expressed support for the Treaty, adding a reasonable proposal to the government: "The very ratification of the Stability Treaty is a weapon of the Bulgarian government to insist the mechanism for entering the euro to be simplified and even abolished,” Mr Kostov, a former PM, said. According to him, with the safeguards enshrined in the Treaty, all other conditions for entry into the euro area have become redundant. The same argument has been launched by Nadejda Neynsky MEP (EPP) during the discussion on EU's economic governance, organised by euinside last November. The proposal did not provoke any interest among the lawmakers who preferred to exchange domestic political attacks and to count how many European countries were ruled by socialist governments at the beginning of the crisis.

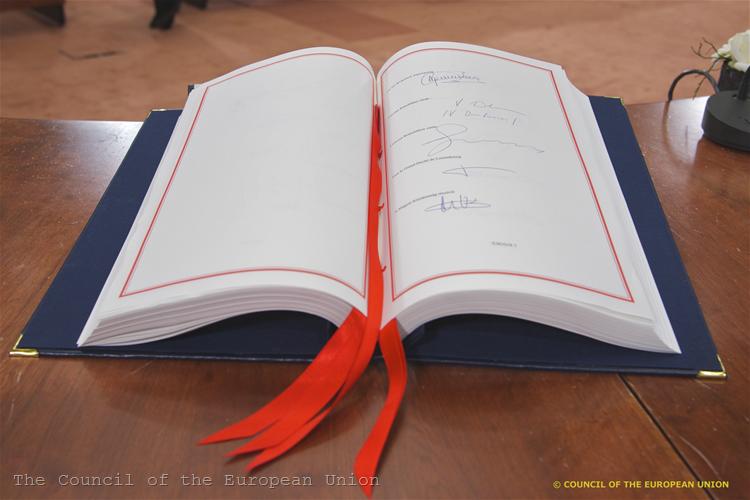

Ultimately, the decision was adopted, as expected, without any changes and without unnecessary passions. The final text of the Stability Treaty is to be approved by the European Council on Monday and signed in early March. Then it must be ratified by national parliaments. According to the latest draft, the treaty will come into force when ratified by 12 countries.

| © The Council of the European Union

| © The Council of the European Union | © European Union

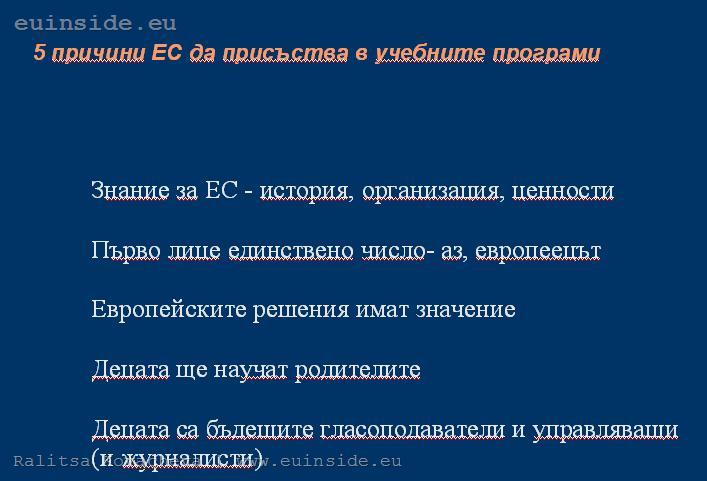

| © European Union | © euinside

| © euinside | © The Council of the European Union

| © The Council of the European Union | © euinside

| © euinside | © EU

| © EU | © EU

| © EU | © EU

| © EU | © EU

| © EU