Why Should the EU be Studied at School?

Ralitsa Kovacheva, April 2, 2012

With this question I tried to provoke teachers from secondary schools in Bulgaria, gathered for a seminar in the EU Information Centre in Sofia. The event was organised by the Information Office of the European Parliament in Bulgaria and aimed Bulgarian MEPs to acquaint teachers with the current European issues and debates. The seminar was eloquently titled "The Future of the European Project: the Cost of 'no-Europe'." Socialist MEP Ivailo Kalfin briefed the teachers with the threats, stemming from the economic crisis, and Stanimir Ilchev MEP (ALDE) told them about the dangers nationalism and populist rhetoric are posing.

With this question I tried to provoke teachers from secondary schools in Bulgaria, gathered for a seminar in the EU Information Centre in Sofia. The event was organised by the Information Office of the European Parliament in Bulgaria and aimed Bulgarian MEPs to acquaint teachers with the current European issues and debates. The seminar was eloquently titled "The Future of the European Project: the Cost of 'no-Europe'." Socialist MEP Ivailo Kalfin briefed the teachers with the threats, stemming from the economic crisis, and Stanimir Ilchev MEP (ALDE) told them about the dangers nationalism and populist rhetoric are posing.

Against this background, my goal was to provoke teachers by telling them that children should study the European Union at school, but not by adding more factual knowledge to their already crammed heads but by giving them proper civic education. They should understand and accept the European values, start talking and thinking of themselves as Europeans, unlike us, their parents, who still feel not exactly and not sufficiently Europeans. Because children are the future voters and future rulers of the country, who will take decisions for Bulgaria and for the Bulgarian positions on European issues.

In this sense, knowledge of the EU should be an integral part of the civic education of children. Its meaning would not be to make them better informed but more active citizens. Growing up as conscious citizens of their country and of the European Union, they will succeed where we fail today - to fully participate in European debates and as a result - our country will be able to form and hold meaningful and productive positions. And knowing that they are citizens of a united Europe will expand their horizons and give them new opportunities to study and work.

Having said all this, I am absolutely aware of the starting point. Bulgarian media landscape is dominated by a few persistent metaphors of Bulgaria's EU membership. Five years after joining the EU, Bulgaria continues to be a member only when it suits her - Brussels is good when it gives and bad when it requires. The media image of the EU (Brussels) has joined those of "Grandfather Ivan" (Russia used to be called like that in Bulgaria) and "Uncle Sam" as another external force affecting Bulgaria`s decision-making process. Bulgarian media persistently describe the European Commission representatives as "Eurocrats", with all the possible negative connotations of this image.

A favourite phrase of the government (not only in Bulgaria) is "Brussels said" - this is how all unpopular measures that could alienate voters are justified. Although not present in all its depth and the necessary activity in Bulgarian media, the popular European dilemma 'national sovereignty vs. "More Europe"' is solved by the media in favour of the national interest (even if it is not clearly defined), especially when it is necessary to demonstrate our European solidarity in financial terms.

As a result of this media environment, two-thirds of the Bulgarians feel uninformed on European issues, according to a Eurobarometer survey from the end of last year. The fact that the situation across Europe is the same should not calm us. Instead, it once again shows the urgent need for knowledge and understanding of European issues. Moreover, in a way that will make the citizens not just better informed but will enable them to actively participate in the current debates and express their position.

However, this cannot happen through the media, because they obviously have made their choice and instead of directing the public agenda, they accommodatingly follow it. To change this, we must start from the beginning - from the classroom. This is the first place where our children become part of society and there they must understand what it means. This means children to know, beside their rights and obligations as Bulgarian citizens, but also their rights and obligations arising from Bulgaria`s EU membership, the opportunities given by the single European market, the possibilities to participate in EU governance, in decision making process, in the current European debates (about the future of European integration, the role of institutions and nation states; the democratic legitimacy). Of course, all this must be served according to children's age and knowledge.

I think if teachers are willing, they can do many things without the need of additional resources, new curricula or textbooks. Whether it is about discussions in the tutorial hour (with appropriate guests invited), or about projects and other extracurricular activities, games, competitions, visits to cultural and other events related to the European Union – it depends on teachers' views and ideas.

Quite expectedly, my words provoked objections by the teachers that the EU was already  studied in schools, although as part of other subjects, and for five years there information boards about the EU in the classrooms. One teacher argued that ultimately children needed to be active and show that they want to know more about the EU. The inadequate teachers' training in European affairs was also mentioned. But after the seminar I received two e-mails in which teachers write that "yes, we teach about the EU at school, but not as this has to be done." The knowledge of the EU and civil education received by the children is "very formal and distant from their age and understanding."

studied in schools, although as part of other subjects, and for five years there information boards about the EU in the classrooms. One teacher argued that ultimately children needed to be active and show that they want to know more about the EU. The inadequate teachers' training in European affairs was also mentioned. But after the seminar I received two e-mails in which teachers write that "yes, we teach about the EU at school, but not as this has to be done." The knowledge of the EU and civil education received by the children is "very formal and distant from their age and understanding."

So now focus should fall onto how to do this, with the clear objective that education is crucial in brining up a new generation of thinking and active citizens.

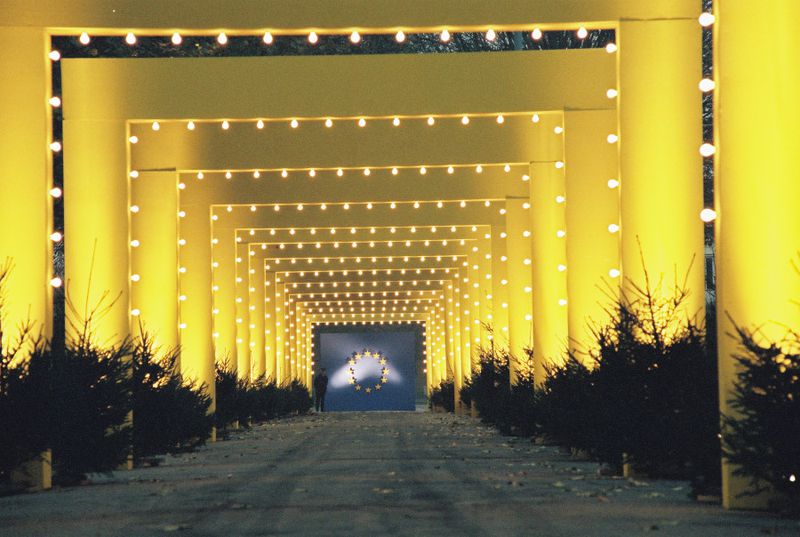

| © European Union

| © European Union | © euinside

| © euinside Krasimir Valchev | © Council of the EU

Krasimir Valchev | © Council of the EU | © euinside

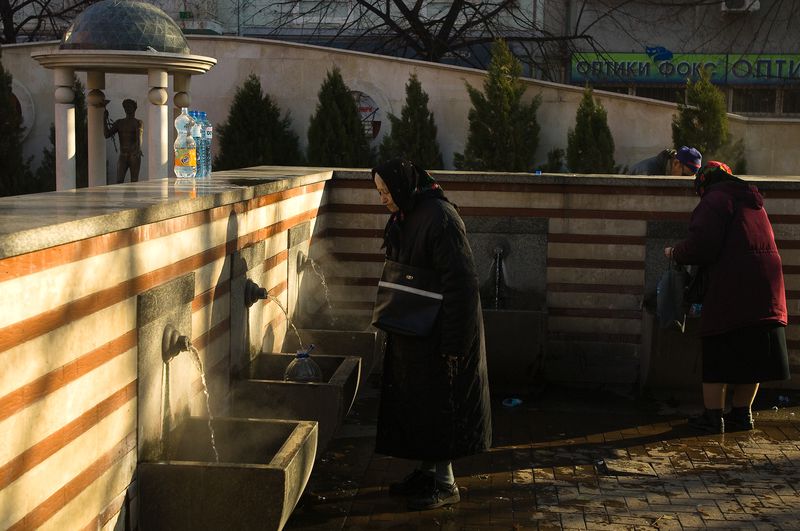

| © euinside | © EU

| © EU | © EU

| © EU