What Future for EU Budget after Brexit?

Adelina Marini, August 23, 2017

That time approaches in the EU when member states will begin talking about money. The seven-year cycle of the common budget is now coming to an end, and as tradition calls for, the talks about the post-2020 cycle will begin two years earlier. This time, however, will be radically different because much water has passed since the last negotiations. One of the largest donors to the European budget - the UK – is leaving the Union and the other 27 are reluctant to increase their contributions, or give up what they have received so far. In addition to this, there is the internal tension between the "old" and the "new" members in terms of European values and the search for a link between them and the European budget. All this implies that the upcoming negotiations will be the hardest ever.

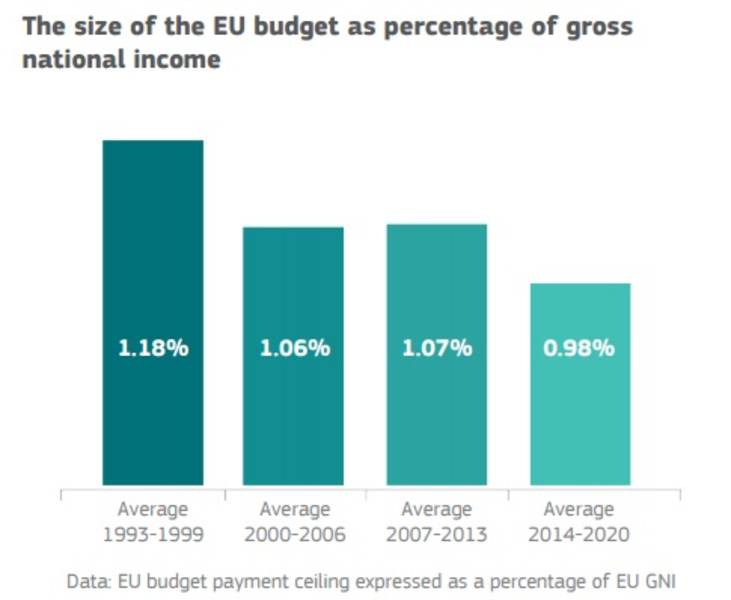

Old priorities (especially after the Brexit), such as the disputes over the Common Agricultural Policy and tackling the effects of the economic and financial crisis, will give way to the new ones - the refugee crisis, common defence, terrorism. It is certain that the absence of the UK will be felt during the negotiations in several directions. The United Kingdom has always had a strong critical approach to the negotiations and has insisted on a budget that is as small as possible, which is to focus more on innovation and defence and not on further subsidies for European farmers. This criticism during the time of David Cameron transformed into Euroscepticism, which in turn led to an unprecedented nominal reduction in the total European budget, although the EU has already expanded considerably (the last enlargement was in 2013 when Croatia joined).

Another aspect is that, despite its scepticism, Britain has always balanced skillfully between new and old members. Now this balance will not be there. The leaving of the UK opens up an opportunity for a complete overhaul of the budgetary framework, including the re-opening of an old and usually overlooked subject - own resources as a source of additional funding for common policies. In addition, an opportunity rises to remove the complex and outdated system of discounts (rebates), which in itself will be a significant integration step forward.

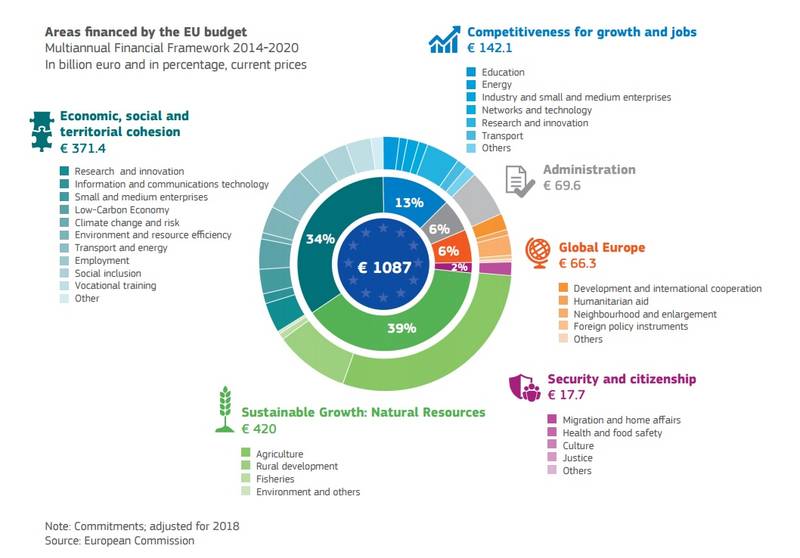

The review of the current financial framework covering the 2014-2020 period revealed several shortcomings in the common budget as the Union faced severe challenges such as the migration/refugee crisis. One of the most important conclusions of the mid-term review of the framework, published in September of last year, is that all the buffers in it have been used up and the limits of each item have been stretched to the maximum to meet the new needs. The total amount of the agreed common budget is 1,087 trillion euro, which represents 1% of the Union's gross national income (GNI).

Another important conclusion is that, owing to the growing needs of the Union, additional instruments have been created, some of which are funded from the common budget. An example of this is the well-known "Juncker" investment plan, with its accompanying strategic investment fund, which is financed from the common budget at the expense of other programs. Since its inception, the European Parliament's concerns that the investment plan will start to compete with the common budget have proved true, which is admitted by the European Commission.

Negotiations on the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) will begin officially next year during the Bulgarian rotating presidency of the Council. At the end of June, the European Commission proposed ideas for reflection before the start of the negotiations. The latest in the series of reflection papers, which is part of the Commission's White Paper on the future of the EU, proposes that the Union's main priorities to be security, solidarity, and the economy. Given that there is agreement among member states that the fight against terrorism is to be conducted at the European level, as well as going towards deep defence integration, the EC believes it is time to decide what role the common budget can play in these areas.

In one of its reflection papers, the EC proposes the creation of a special new program to finance defence research and development and joint purchasing of military equipment. The budget for the future defence program is proposed to be 500 million euros a year. The economy should continue to be a top priority for the next budget, but with a slightly different focus - social inequality. The Commission proposes that member states should focus on reducing the economic and social disparities between member states, as well as internal inequality. It is proposed to strengthen the link between the implementation of reforms and EU funds.

In one of its reflection papers, the EC proposes the creation of a special new program to finance defence research and development and joint purchasing of military equipment. The budget for the future defence program is proposed to be 500 million euros a year. The economy should continue to be a top priority for the next budget, but with a slightly different focus - social inequality. The Commission proposes that member states should focus on reducing the economic and social disparities between member states, as well as internal inequality. It is proposed to strengthen the link between the implementation of reforms and EU funds.

A half-hearted mention is made of the need for further reform of one of the most resource-intensive programs in the common budget - the Common Agricultural Policy. It becomes more and more complex to manage, which hampers its execution and leads to delays. The EC's conclusion is that radical approach is needed to simplify implementation and increase the flexibility of the program. In previous budget cycles, the CAP was the largest Community policy for which the EU spent almost half its budget. In this budget cycle, it is noticeably shrunk and is no longer the largest. It is in the second largest item "Sustainable Growth: Natural Resources", whose budget is 420 billion euros. The share of the CAP in the total budget is 37.8%.

Another major community policy - the cohesion policy - is also not spared. The Commission proposes directly that it is linked to the European values system. "There is hence a clear relationship between the rule of law and an efficient implementation of the private and public investments supported by the EU budget", the document says. The Cohesion Policy budget for the current budget cycle is 351.8 billion euro, with its share of the total budget being 32.5%. Along with the problems with the rule of law in Poland, as well as with Hungary and other "naughty" member states, there are more frequent calls to look for a direct link between EU funds and the rule of law.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel has recently adamantly denied that such a connection should be made but we still have to wait for the parliamentary elections in Germany in September to see what the attitudes will be. The new member states, as in the previous negotiations, have united in a "cohesion front" and have already made it very clear that they will not allow their funding to decline. According to the EC, economic cohesion must be a top priority not only between new and old Europe. This is also a top priority in the ideas for deepening the integration in the euro area.

Beyond the ideas for reform of the current main headings and policies of the Community budget, the EC proposes five scenarios for the future EU budget that respond to the options for the future of the Union as described in the EC White Paper for the future: preserving the status quo; loosening the union; a multi-speed EU; radical change; deepening of integration.

Preserving the status quo

In this scenario there will be no sudden movements. The main spending items will remain - the Common Agricultural Policy and the economic cohesion among the different regions of the EU - and the new priorities will be internal and external security; migration and border control; defence. A closer link between the European Semester and the implementation of structural reforms is also proposed, as well as dropping the current rebate system and searching for other sources of revenue in the common budget. Currently, several countries benefit from concessions, with the British rebate being the largest - the UK receives back 66% of its contributions, which is the difference between its contributions and what it gets back from the budget.

Denmark, The Netherlands, Sweden and Austria also receive one-off deductions. Sweden, The Netherlands and Germany are benefiting from lower VAT rates, which are one of the pillars for calculating the EU's own resources, but we will get back to that in a little while.

A loose union

The second scenario is intended for a looser Union and provides for a significant reduction in Community policies. For the CAP, the Commission proposes support only for those farmers experiencing specific problems such as small farms, mountainous areas, and sparsely populated areas. Under this scenario, cohesion policy is provided to be limited only to the most underdeveloped countries and to cross-border cooperation. In this case, the common funding of new priorities - security, border control, migration and defence - is eliminated.

The most successful EU programs such as Erasmus, research and development programs and some others are also removed. The budget for the Erasmus+ program for 2014-2020 is nearly 18 billion euro and funding for the "Horizon 2020" research program is 80 billion euro. This scenario also suggests removing rebates.

A multi-speed budget

The third option the EC proposes about common finances envisages the budget to be split depending on integration speeds. The basic framework is from the first scenario, adding additional budgets and innovative funding for the European Public Prosecutor's Office (which is being constructed by only a group of member states), the euro area, and the other new policies currently underway. It is also proposed to add new resources, but not for all, such as the financial transactions tax, which will be collected by only 10 member states at this stage - Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Greece, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain.

The third option the EC proposes about common finances envisages the budget to be split depending on integration speeds. The basic framework is from the first scenario, adding additional budgets and innovative funding for the European Public Prosecutor's Office (which is being constructed by only a group of member states), the euro area, and the other new policies currently underway. It is also proposed to add new resources, but not for all, such as the financial transactions tax, which will be collected by only 10 member states at this stage - Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Greece, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain.

A radical change

The fourth scenario envisages an overall change in the concept of the common budget so as to focus it on the new priorities. This means reducing direct CAP payments and focusing on the most needing farmers, as in the second scenario. Cohesion policy is also projected to be limited to the poorest regions. More money is to be allocated to the new priorities - security and defence - as well as some existing priorities such as transport and energy networks, digital economy. In this scenario, the EC also proposes a connection between results under the European Semester and funding.

Financing this scenario is proposed to be done by removing rebates, abolishing or reforming VAT-based own resources, and introducing new own resources such as a green tax, financial transaction tax, a common consolidated corporate tax base.

A large ambition

The fifth scenario foresees a sharp increase in the common budget, which includes an increase in the CAP budget, a common defence and security budget, a common budget for the euro area and a European Monetary Fund, more money for foreign policy. Cohesion policy is proposed to be preserved in its current form. Under this scenario, the EC has no concrete ideas about where to get the money for it. There is just a mention of other sources of revenue or taxes.

A reform of own resources

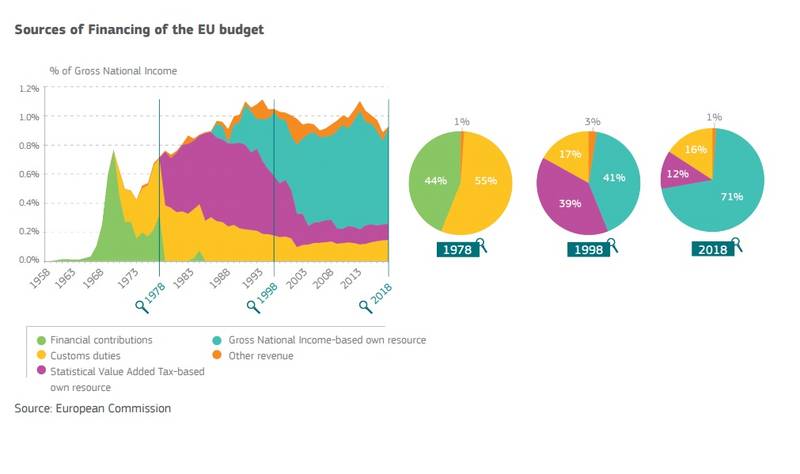

Own resources always appear as a topic in each negotiation of the EU's multiannual common budget, but until now no one ever wanted to touch this house of cards. But now the situation is different and everyone is already aware that a major overhaul is needed so that the common budget adapts to changes in the EU. The June reflection paper of the European Commission has taken into account all the recommendations of the high level group tasked with analysing the possibilities of increasing EU own resources without treaty change or increasing contributions by member states.

The group was headed by former Italian prime minister and commissioner Mario Monti, and two Bulgarians worked with him - former EC Vice-President Kristalina Georgieva and former Foreign Minister and MEP Ivailo Kalfin. The group also included the European Commissioner for Tax Affairs Pierre Moscovici (France, Socialists and Democrats) and the right hand man of EC president, Frans Timmermans (Netherlands, Socialists and Democrats). The group published its final report in December of last year. One important conclusion in the report is that EU own resources are often interpreted differently in national budgets, making comparisons between member states impossible, and another, and much worse, consequence that this is often the basis of conflicts during budget negotiations.

The own resources that feed the common budget at present are three: revenue from customs duties at the external borders of the EU, a common resource based on VAT, and the deduction from gross national income, the calculation of the last resource being dependent on the first two. Only four member states define their contributions to the general budget as EU own resources in their national budgets. These are France, Germany, Austria and Bulgaria. The others account for them as direct public spending but with serious differences. In Belgium and Luxembourg, for example, VAT-based contributions are considered revenue and GNI contributions as expenditure. In most member states, contributions to the EU budget are accounted for as government spending.

The reason is that VAT-based and GNI-based own resources are often described as national contributions in EU budget documents and in the annual financial statements as they are the result of statistical data. VAT revenue, for example, first enters the national budgets and, hence, distortions start. For this reason, VAT-based own resource was never considered a genuine own resource. Therefore, in its reflection paper, the EC also proposes revisiting it and replacing it with other own resources.

Another big problem outlined by the workgroup is that European added value is not taken into account at all, and these are the benefits that member states receive thanks to Community policies and which they would otherwise not have been able to obtain by themselves. Member states  usually approach the negotiations on the common budget as an ordinary budget balance. Thus, every euro spent in a given country is considered to be an expense for others.

usually approach the negotiations on the common budget as an ordinary budget balance. Thus, every euro spent in a given country is considered to be an expense for others.

The report recommends first to harmonise EU own resource accounting and to introduce a measure of the collective benefits of European Community policies, cross-border effects and benefits secured abroad. This will give a much clearer picture of the European budget, instead of it being looked at as a zero-sum game. The report also recommends that, when discussing the reform of the European budget, account should be taken of the specificities of the EU institutional framework and that its budget should not be considered in the light of national, regional or local budgets.

The report proposes the following candidates for own resources: carbon dioxide tax; revenues from carbon emissions trading; fuel taxation; electricity tax; a common consolidated corporate tax base (only for those who introduce it); a tax on financial transactions or a tax on financial activities; seigniorage. The group also recommends eliminating discounts and rebates. Whether some of these proposals will be taken into account during the negotiations will depend on the level of ambition that member states will choose - one of the five scenarios or a combination of several.

Translated by Stanimir Stoev

Federica Mogherini | © Council of the EU

Federica Mogherini | © Council of the EU | © Council of the EU

| © Council of the EU Luis De Guindos | © Council of the EU

Luis De Guindos | © Council of the EU