Bulgaria Remains a Developing Economy

Adelina Marini, April 20, 2015

The International Monetary Fund presented last week its spring world economic outlook. Nothing unusual if you have watched the news. There are signs of an economic momentum in the euro area which reflects the low oil prices and the favourable financial conditions but, of course, the risks of a prolonged low growth and low inflation remain. Excluding the nuances aimed just for nerds nothing new under the sun, you might say. While I was reading the outlook, however, I found out that there is something new and it is very important. A significant change has happened in Europe in the past 15 years.

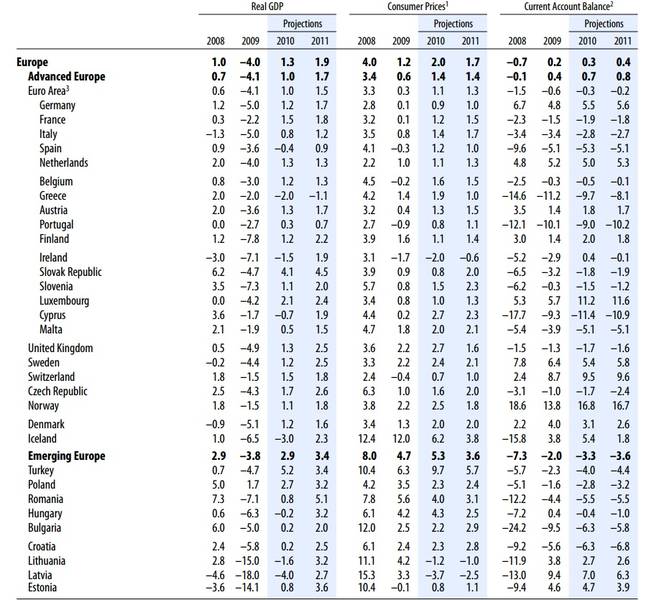

This is the transition from a developing economy to an advanced one in Europe. The old terms Eastern and Western Europe are no longer valid, which actually used to reveal precisely the difference of economic development. Currently other terms are in use - "advanced Europe" and "developing/emerging Europe". In the past 15 years, Bulgaria has remained in the latter group with a perspective to remain there in the coming 15 years too whereas the big change has happened in the other member states that joined the EU 3 years earlier than Bulgaria. In 2005, a year after the big bang enlargement of the EU, when the Union was joined by 10 new member states 8 of which former communist countries (i.e. of the same economic and social calibre as Bulgaria), in the group of developing and emerging Europe was the entire Central and Eastern Europe. This means all the new EU member states.

In 2010, when Bulgaria, too, was already a member of the EU, in the advanced part of Europe were all the euro area countries, including Slovakia and Slovenia. However, the membership to the currency club is not the only reason why a former communist country can receive a ticket to join the advanced nations as one can easily think while watching the data. This same 2010, which was the stormiest since the beginning of the eurozone crisis, the Czech Republic was already among the advanced nations.

And in 2015, in the advanced group can be seen the Baltic states which are now all of them part of the euro area. In the category "developing/emerging Europe" have remained Bulgaria, Romania, Poland and since recently Croatia in the company of the non-EU countries, like Serbia, the other Western Balkan countries and Turkey.

This fact is not appropriately reflected in the IMF economic outlook where in 2005 the report says on Bulgaria and Romania, which on 25 April the same year signed their accession treaties but were still outside the EU, that it expected strong economic growth for the two countries driven by fast credit growth. It is warned, however, that as a result their current account deficits will continue to be high which requires tight fiscal policy and management of the wage and credit growth. The IMF said back then that the two countries needed to do structural reforms aimed at improving the investment climate. It is explicitly pointed out that they should accelerate the fight against corruption to ensure smooth accession to the EU in 2007.

Five years later (2010), Bulgaria does not get so much attention in the outlook excluding the often mentioned issue of the excessive current account deficit. A disease which at the time Latvia and Lithuania also suffered of. In 2015, Bulgaria is not mentioned at all as a specific case. Instead, the European Commission makes in-depth analyses of all the EU economies as part of the European semester. In its report on Bulgaria this year, as euinside wrote, a dim picture is drawn of the Bulgarian economy suffering from the same but now much deeper problems (excluding the current account deficit) - no progress in the fight against corruption despite the fact that the country is under special monitoring, no reforms to improve the investment climate which is why there is an outflow of investment, no reforms of key systems that can boost the economy and can ensure prosperity in the longer term, such as education, the pension system and the judiciary.

This dim picture is a continuation of previous analyses when the Bulgarian economy noted several nuances of grey. The big difference is that in 2013 the Commission believed that the growth of the Bulgarian economy is much below its potential whereas in 2015 it says that its potential is low because of complicated regulation and weak administrative capacity, too high costs for businesses, high energy intensity in a combination with low energy efficiency, poor quality of the rail and road infrastructure.

Moreover, the Commission has this year raised the alert level for Bulgaria from second to fifth where it is in one group with long-term non-reformers such as France, Italy and Portugal which went through an adjustment process. In this group is also Croatia which has been in a recession for six years. The reason for this change is not only the lack of change of the conclusions about Bulgaria's economic situation but also the KTB case (the Commercial Corporate Bank) which is an emanation of the doing-nothing policy in the country. Unless something changed in policy-making Bulgaria will certainly be in the category "developing/emerging Europe" for another five years and it is very likely that by the time Romania and Poland would have left this category. Or Croatia for that matter.

Why? Because none of these countries suffers from the deeply rooted problems Bulgaria does - a ruling oligarchy, a blossoming political corruption in addition to the usual one, a lack of rule of law. All of these are factors that prevent the development of the economy and therefore of the rise of the standard of living of the citizens.