Eurozone, Britain and the Rest

Adelina Marini, July 3, 2012

Europe at three speeds emerged on Friday morning. This became possible after the EU leaders succeeded to agree on the direction in the future, with which to try and exit the whirlpool of the eurozone crisis. The summit took place as usually in the past few months in several layers, each of which had its own dynamics - the Polish PM, for instance, was concerned - and with good reason - that might happen what happened - Europe to disintegrate into separate communities with the tendency those to start moving away instead of getting closer; the Bulgarian prime minister was interested everything to end quickly so that he did not miss the Germany-Italy football semi final, while Britain was trying to stay in the game and again played the role of the stick in the wheels of the European integration, but this time unsuccessfully.

Europe at three speeds emerged on Friday morning. This became possible after the EU leaders succeeded to agree on the direction in the future, with which to try and exit the whirlpool of the eurozone crisis. The summit took place as usually in the past few months in several layers, each of which had its own dynamics - the Polish PM, for instance, was concerned - and with good reason - that might happen what happened - Europe to disintegrate into separate communities with the tendency those to start moving away instead of getting closer; the Bulgarian prime minister was interested everything to end quickly so that he did not miss the Germany-Italy football semi final, while Britain was trying to stay in the game and again played the role of the stick in the wheels of the European integration, but this time unsuccessfully.

Britain

UK this time too, as in December, won a battle but lost the war. If you remember, in December when the fiscal compact was being negotiated, the country decided to stay out, which Mr Cameron pronounced as a huge achievement but it in fact it laid the foundation of the loss he endured on the Brussels front on Friday. And if then Britain still looked big, half a year later it looks smaller and smaller from the point of view of the processes in Europe. In fact, it is more precise to say that both times Britain won short-term domestic battles. This time London won the battle for the European patent, being  awarded to host one of the three divisions of the European patent court (Paris, London and Munich). It is yet to assess the long-term impact of these decisions for the future of the country in a global and European context.

awarded to host one of the three divisions of the European patent court (Paris, London and Munich). It is yet to assess the long-term impact of these decisions for the future of the country in a global and European context.

That David Cameron's government realises the scale of the disaster is visible from his article, published in the Sunday edition of the conservative daily The Telegraph. The article indicates the desperation of the British prime minister after this time the indeed crucial EU summit. Some analysts and media interpret it as a U-turn in David Cameron's policy and as a bending under the pressure of his own party and the British society to hold a referendum on whether Britain should stay in the EU or not. You probably remember that Cameron was subjected to friendly fire in his own party in October, just when it was for the first time spoken of saving the eurozone with tools that would require more concessions by all. Then, during parliamentary debates and voting for a referendum, against Cameron voted 79 of his backbenchers, which led to the resignations of two members of the cabinet.

Ultimately, those who wanted referendum did not win but the question remained open. Pretty much aware with what had been achieved on Friday and what he was to face this week, David Cameron decided to outrun the events and came up with a proposal not simply for holding a referendum on "for" or "against" the country's membership in the EU. "It is vital for our country — for the strength of our economy, for the health of our democracy and for the influence of our nation — that we get our relationship with Europe right. We need to be absolutely clear about what we really want, what we now have and the best way of getting what is best for Britain. We need to answer those questions before jumping to questions about referendums".

These words of the British premier show very clearly that this is not about a retreat from his vision on referenda in general, but about realising the facts: "First, we need to recognise that Europe is changing — and fast . The single currency is driving a process that will see its members take more and more steps towards fuller integration". And this is something Britain is not ready for and is unlikely to be ready any time soon. The only reason why Britain is a member of the EU is also explained very simply and clearly in the article: "As a trading nation Britain needs unfettered access to European markets and a say in how the rules of that market are written. The single market is at the heart of the case for staying in the EU. But it also makes sense to co-operate with our  neighbours to maximise our influence in the world and project our values of freedom and democracy".

neighbours to maximise our influence in the world and project our values of freedom and democracy".

Britain is yet to face tough months ahead, during which the country has to decide what to do. The easiest, hasty and harmful decision would be for the sake of a few more votes to subject to a referendum on "yes" or "no" to EU membership, during which the citizens will punish the government for what is considered anti-social spending cuts, budget restrictions, for the banking scandals and the overall economic situation, which is not rosy at all, in spite the fact that UK has managed to come to the surface and is scoring economic growth, although strongly hindered by the eurozone crisis, with which accounts for almost half of trade relations.

It is clear even now that Britain with an isolationist policy will lose even more influence in the EU, hence it will lose one of its main benefits from membership - to participate in the writing of rules and to multiply through the EU its global influence. The future belongs to big formats and Britain, in spite of its efforts in the past 2 years to work individually on the global scene, does not possess the powers to compete for a place under the sun. The situation is very well described by Jo Johnson, a conservative MP, in an analysis for the London-based Centre for European Reform think tank. In it Mr Johnson points out that Britain is facing a tough choice: on the one hand closer coordination of economic and fiscal policies among the eurozone members, which could lead to a gravitational pull of decision-making towards the inner core. "Although other countries value British membership of the EU, they do not do so at any price. It is

important for Britain to realise that it is no longer seen as bringing as much to the European table as it once did".

The rest

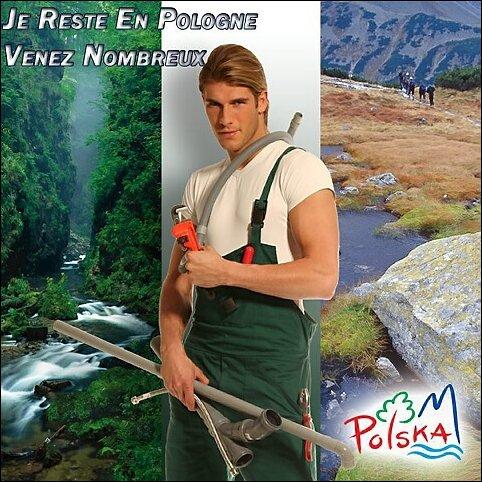

Britain's position, as a balancer among the toughest positions in the EU, is gradually  being overtaken by Poland - the country with the most dynamically developing economy in the entire European Union, and the country which illustrates the best the benefits of European integration. Poland is also the country which fights with teeth and claws to prevent the separation of the eurozone as an individual process of integration with growing isolation of the rest. But Poland is in this role quite lonely. The new member states that are at its level are not many to be able to support its battle with the growing European core. The Czech

being overtaken by Poland - the country with the most dynamically developing economy in the entire European Union, and the country which illustrates the best the benefits of European integration. Poland is also the country which fights with teeth and claws to prevent the separation of the eurozone as an individual process of integration with growing isolation of the rest. But Poland is in this role quite lonely. The new member states that are at its level are not many to be able to support its battle with the growing European core. The Czech  Republic shares quite similar to the British positions and was the second country to refrain from signing the fiscal compact. Hungary is in a dire economic crisis and with not a very good authority in Europe after the aggressive behaviour of its prime minister Victor Orban during the Hungarian Presidency last year and then on the occasion of the reform of the legislation concerning the freedom of media, as well as the independence of the central bank and the judiciary.

Republic shares quite similar to the British positions and was the second country to refrain from signing the fiscal compact. Hungary is in a dire economic crisis and with not a very good authority in Europe after the aggressive behaviour of its prime minister Victor Orban during the Hungarian Presidency last year and then on the occasion of the reform of the legislation concerning the freedom of media, as well as the independence of the central bank and the judiciary.

Bulgaria and Romania have turned into introvert, non-reforming and growingly isolated countries, whose agenda can hardly be recognised as European. Their reactions at European level are more and more inadequate, which is why no one is attentive to their positions. And it can hardly be different with remarks by the Bulgarian prime minister of the type "we are always for the German position", without this being sufficiently defended - why, how and how long. Or with disputes between the president and the prime minister of Romania who of them should attend the EU summit. What is  left for Poland is only the Baltic states as logical allies. They are a good choice because they bring the support of the Nordic European front of countries who want the eurozone to survive but are against this to happen at any price.

left for Poland is only the Baltic states as logical allies. They are a good choice because they bring the support of the Nordic European front of countries who want the eurozone to survive but are against this to happen at any price.

Poland analyses the European Union and the benefits from it in exactly the same way as Britain but with the opposite mark. In an article for the most circulating Polish daily "Rzeczpospolita" and then re-published in the EUobserver, the centre-right Polish MEP Jacek Saryusz-Wolski writes: "We observe with great concern the birth of a two-level solidarity within the Union: one for those inside and the other for those outside the eurozone. But the sovereign debt and banking crisis affect all EU countries, not just the Euro-17. This happens through the mechanisms of the EU single market: the free movement of goods, services and capital. Banks from the Central and Eastern Europe, which are not members of the euro area, are to a large extent (about 70 percent in Poland), held by banks from the eurozone, and the effects of the crisis are transmitted directly, not only through trade".

The Polish fears explains at best analyst Konstanty Gebert, chief of the Warsaw office of the European Council in Foreign Relations (ECFR). On the eve of the summit he wrote: "The worst possible outcome, which it believes might occur after an uncontrolled default of one of the 17, would be a radical tightening of the remaining euro zone of 16 members or less, which would amount to the creation of a two-speed Europe. The second-speed zone would unavoidably then become a second-class zone, with its members, including Poland, adopting different survival strategies. Ultimately it would mean they have to try to rejoin the core EU at great effort, with questions over how and when this might be possible".

It will definitely be a pity for a country like Poland, which walked with big strides the hard path of transformation from socialism to developed market economy, which is now in the 21st century. It will be a pity for the huge contribution which the European integration had for the democratically instable countries in Europe, but the circumstances globally are such that require the rightest and oriented to the future decision must be taken. Whoever can adapt, they will do it, whoever cannot - they should accept the results and set aside some time to analyse them.

| © Governo Italiano

| © Governo Italiano | © EU

| © EU | © null

| © null