From Magna Carta to Indyref

Adelina Marini, October 14, 2014

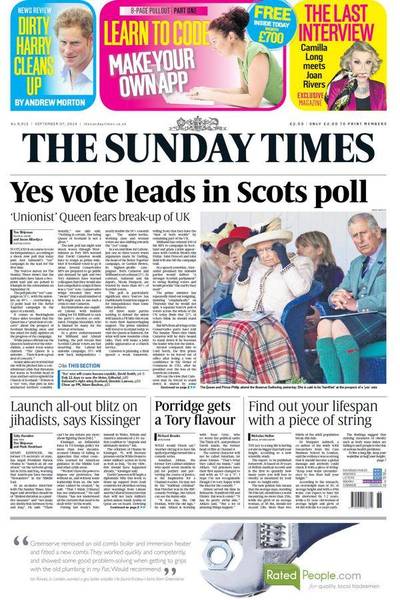

A 307-years-old union was put to its biggest test since its inception but the British have again proved that they are the creators of the modern democracy. The referendum on 18 September on Scotland's independence was a true lesson in democracy, especially at a time when it is seriously threatened across the globe but in the EU as well. The lesson is a multi-layer one and does not affect the United Kingdom only. It is a lesson for the EU as a union, for its member states as having agreed to walk together toward a common goal - freedom, democracy, rule of law, equal rights, prosperity - and for all the others that are in the EU's closest neighbourhood and have aspirations to get closer.

A 307-years-old union was put to its biggest test since its inception but the British have again proved that they are the creators of the modern democracy. The referendum on 18 September on Scotland's independence was a true lesson in democracy, especially at a time when it is seriously threatened across the globe but in the EU as well. The lesson is a multi-layer one and does not affect the United Kingdom only. It is a lesson for the EU as a union, for its member states as having agreed to walk together toward a common goal - freedom, democracy, rule of law, equal rights, prosperity - and for all the others that are in the EU's closest neighbourhood and have aspirations to get closer.

A lesson that was taught only several months after Vladimir Putin announced the final return of totalitarianism in Russia with the illegal annexation of Crimea. A lesson held in the year when Serbia is expected to begin accession negotiations while it is trying to "normalise" its relations with its former province Kosovo. A lesson that creates a stark contrast to Viktor Orban's new illiberal doctrine, announced in end-July.

Next year will mark the 800th anniversary of the signing of Magna Carta - the document that marks the beginning of the rule of law and of democracy based on that founding principle. In 1215, a group of feudal owners united against king John of England demanding to limit his rights over their lands and to get more liberties. After long negotiations, intrigues and treacheries, the document was signed and although it was aimed at putting out the then political crisis nothing was ever the same after it. Now the rule of law is cemented in Article 2 of the Treaty of the EU and it seems like a winking of history that a year before this jubilee a referendum took place that produced a similar result - the Scots have received a commitment for serious changes in their relations with Westminster.

David Cameron's complex poker

It should not be forgotten, however, that it came to all this because the referendum is part of a bigger and much more complicated game that does not affect the Scots only. Prime Minister David Cameron belongs to that group of politicians who have not yet realised what had changed after the Iron Curtain fell and the entry into the digital era. While the geopolitical shifts were taking place, globalisation, the incursion of the Internet, politicians continued to think that they are the only ones who set the agenda together with the mainstream media. They missed to learn the lessons from the Arab spring which was possible thanks to the social networks and they also thought that the developments there were something that would not happen in Europe because we already have democracy here. However, the level of democracy varies from country to country in the EU and in some places there is a process of dismantling it. A process which is quite the opposite to the democracy the EU has been developing at institutional level.

In Europe, too, people are becoming more and more conscious that their opinion coincides with the opinion of thousands of others like them but not with the agenda of traditional political parties. Therefore, new political factors have emerged. A group on Facebook is now completely enough to stage a large protest or to give birth to a new political force, a non-governmental organisation or simply to impose a new issue on the agenda of the society that has been ignored by mainstream media and therefore by politicians.

Completely unaware of this fact, David Cameron found himself facing the biggest challenge his party ever had after the Thatcher era - the emergence of a new political force on the British political stage - the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), led by Nigel Farage, a populist. The very growth of UKIP, which started not from London or any other part of the UK but from Strasbourg (the European Parliament), is a proof how many things David Cameron and his Conservatives have omitted in the past 20+ years. This is valid not only for the Conservatives, as a matter of fact, but also for the Labour and the Liberals. They omitted that the EU has significantly changed with their assistance - action or inaction. The Union is now much more integrated and in the euro area the 2008 crisis has revealed a much deeper integration. This interconnectedness showed that despite all of its opt-outs, Britain is much more closely bound and even dependent on the developments on the Continent than it would like to.

Completely unaware of this fact, David Cameron found himself facing the biggest challenge his party ever had after the Thatcher era - the emergence of a new political force on the British political stage - the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), led by Nigel Farage, a populist. The very growth of UKIP, which started not from London or any other part of the UK but from Strasbourg (the European Parliament), is a proof how many things David Cameron and his Conservatives have omitted in the past 20+ years. This is valid not only for the Conservatives, as a matter of fact, but also for the Labour and the Liberals. They omitted that the EU has significantly changed with their assistance - action or inaction. The Union is now much more integrated and in the euro area the 2008 crisis has revealed a much deeper integration. This interconnectedness showed that despite all of its opt-outs, Britain is much more closely bound and even dependent on the developments on the Continent than it would like to.

And how much does the UK like to?

This is the question which, especially now after the referendum in Scotland, needs more than ever to be answered because it is obvious that between London and Brussels the same tension is boiling that was accumulating between London and Edinburgh for decades. Consciously or not, David Cameron turned the Scottish referendum into a general rehearsal for a possible vote on the kingdom's stay in the EU. And if until recently this was a matter of party decision entirely, now it should be tabled by all the British political forces - do we want to stay in the EU or not? This is necessary not only because of the vote in Scotland but also because of the tensed relations between the Island and the Continent which, again, we should thank David Cameron for. Quite telling of how nothing is the same in the relations between London and Brussels was the hearing of the British candidate for EU commissioner Jonathan Hill in the European Parliament two weeks ago.

He was the only one subjected to the humiliation to appear twice for a hearing because of incompetence. The problem is, though, that Jonathan Hill was not at all the only candidate who demonstrated incompetence or lack of legitimacy to take the proposed post. Pierre Moscovici, the French candidate, was completely unable to reveal his capacity because he was forced to fight back the attacks of MEPs that he had failed in France. And Tibor Navracsics comes from a government that does not abide by Article 2 of the Lisbon Treaty which very clearly formulates the European values. Nevertheless, for the two a deal was struck by the two biggest political parties in the EU - the Socialists and the EPP. While Jonathan Hill stood as if he was an alien body to all this.

The scandal with his audition caused a new wave of calls for the UK to leave the EU. And although his nomination was in the end approved, the Commission is to be voted by the European Parliament very soon. Hardly any serious problems can be expected but it was more than clear that the European Parliament tried to punish UK and David Cameron personally for his peremptory behaviour in the EU which was quite the opposite to the behaviour the British prime minister had in the last weeks before the referendum in Scotland. Certainly, the problems in the relations between London and Brussels are far from over yet. On the contrary, they are about to begin. This will not change until the question whether Britain wants to stay in the EU or not is answered clearly. That is why Cameron and the other political leaders in the country should speak clearly on the issue and set a date. This issue has long ago went beyond the needs of the Conservatives to be re-elected. This is now a common European necessity.

Mr Cameron agreed to the referendum in Scotland before his famous European (or rather anti-European) speech of January 2013 when he announced that he wanted a radical reform of the EU and threatened that if he would not get it he would hold a referendum on UK's stay in the Union in case, of course, he were to be re-elected in 2015 - the anniversary of Magna Carta. After the announcement of the results he said he was a "passionate believer" in the United Kingdom. "I wanted more than anything for our United Kingdom to stay together", he added. David Cameron underscored that he was a democrat and that was why he respected the right of the Scottish National Party (SNP) to hear the voice of the people. This is a message aimed mainly at the EU. I hope that he will not betray his democratic views and will allow the EU to participate in the campaign on a possible referendum on Britain's EU membership. I also hope that the EU, for its part, will, too, reveal itself as a "passionate believer" and someone who desires "more than anything" Britain to stay in the EU.

According to British analysts and journalists, David Cameron underestimated untill the very last moment the significance of the Scottish referendum and that it was possible the result to be different than what London wanted - keeping the union together. Although some European leaders expected the outcome holding their breath, there was, too, a similar underestimation in the EU in terms of a possible Brexit. The responsibility, again, is David Cameron's because he put a condition for such a referendum, but given the consequences from the Scottish voting, there needs to be more clarity on whether there will be or will not be an exit referendum. One of these consequences is the boost of separatist movements in Spain.

Catalonia is not Scotland

Now everything that is being done on the Continent will be levelled up to the standards set in the Scottish referendum. And the most important thing about it was the debates. After the decision was made a referendum to take place with the famous Edinburgh agreement of October 2012, the campaign started. It lasted two years during which all sorts of arguments could be heard. And although most of the time the referendum was strongly underestimated in London, the public had enough time to hear all the pros and cons about remaining in the 307-year-old union. This should serve as example for the EU when it comes to a referendum on UK's staying in the EU and for Spain. The Catalans demanded a referendum for independence to take place on November 9th. But the time by then is very insufficient to hold a reasonable debate (by the time this article was translated the news broke that the Catalans have withdrawn their demand).

Now everything that is being done on the Continent will be levelled up to the standards set in the Scottish referendum. And the most important thing about it was the debates. After the decision was made a referendum to take place with the famous Edinburgh agreement of October 2012, the campaign started. It lasted two years during which all sorts of arguments could be heard. And although most of the time the referendum was strongly underestimated in London, the public had enough time to hear all the pros and cons about remaining in the 307-year-old union. This should serve as example for the EU when it comes to a referendum on UK's staying in the EU and for Spain. The Catalans demanded a referendum for independence to take place on November 9th. But the time by then is very insufficient to hold a reasonable debate (by the time this article was translated the news broke that the Catalans have withdrawn their demand).

After two weeks of campaigning the outcome in Scotland reveals a very serious division on this crucial issue - 55% of all the 85% who voted said No to independence, while 45% remained very disappointed with the outcome. Currently, the opinion polls in Catalonia show a significant support for independence (circa 80%) but this is without all the arguments having been heard and the government in Madrid is not making the task any easier. Instead of initiating a dialogue, the capital is practically convincing the Catalans of the need to leave. Unlike the Scottish referendum, in Spain there is much less talk on the pros and cons of secession. In Scotland, despite the two years of campaigning, the Scots were not completely certain whether they would stay in the EU or not. In January this year, European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso said in an interview with the BBC that if dissociated Scotland would be a new state which means that it would have to apply for EU membership.

The application should be approved by all the member states which, in Mr Barroso's words, would be very hard, especially when it comes to a state that comes out of a member state. "We have seen Spain's opposition to Kosovo which is a similar case", Mr Barroso recalled. Legal experts quote Article 49 of the Lisbon Treaty which says that every European state that respects the values in Article 2 and is committed to promoting them may apply for EU membership. It is explicitly stated that the application requires unanimous approval by the Council. The European Parliament's consent is also necessary which makes the situation even more complicated. One of the key issues in the last stages of the campaign in Scotland was the common currency. Scotland's first minister Alex Salmond, the main driver of the referendum, wanted after a possible secession the future state to keep the sterling as its own currency but London disagreed.

Tha Catalan case is even more complicated because Spain is a member of the euro area and a possible independence of parts of a member state could seriously shake the common currency, which was demonstrated by the decision of the Fitch credit rating agency to downgrade Catalonia's credit rating to BBB- because of the possible referendum. The economic arguments are a significant part of the debates, which are obviously much needed in Spain but in the EU as well. This is the biggest lesson from the Scottish referendum.

Houston, we have a problem

The European Union is embraced by strong nationalist, anti-establishment and eurosceptic moods, illustrated very clearly during the European elections this year. Depending on the historic differences from the past 70 years, the power and scale of these movements varies throughout the EU, but undoubtedly they are a threat to the status quo. The demands for referenda are a signal that for too long have been ignored problems that are important to people and the EU showed that it cannot be a solution to them. But it will be a mistake to interpret this signal as a purely national issue, especially after the European elections last May. The discontent that has been accumulated in the past decade from the enlargement and the crisis is a result of the EU being too distanced from the citizens and of the national discourse being usurped by the national point of view only. With the proved economic interdependence after the 2008 crisis, especially in the euro area, the absence of the EU from the national debates is a deprivation of the citizens of a legitimate point of view. For that are responsible both the national political f orces but Brussels as well, which has turned instead of an appendage to national politics into its opposition or even an enemy.

orces but Brussels as well, which has turned instead of an appendage to national politics into its opposition or even an enemy.

That is why, it will be crucial to learn all the lessons from the Scottish referendum but not because we want to avoid it being repeated or similar actions to take place elsewhere in the EU but because we want the voice of the citizens to be heard and to offer them a solution to their problems - be it on national or European level. One of the biggest lessons from the voting was that it provoked the three main political parties in the UK to make a vow to the Scots. The leaders of the three parties - the Conservative, the Labour and the LibDems - vowed to give new powers to Scotland. It is high time the EU did the same. The approaching anniversary of the Magna Carta should serve as a reminder that hearing the voice of the citizens could only be to the benefit for the development of society. The new European Commission and the European Parliament have a very important mission - to prove that 800 years are not in vain and that the model is not Russia but the UK where the force of the argument is bigger than the force of soldiers' boots.

And although the Union between the EU and UK is many times younger (only 41 years old) than that between London and Edinburgh, the historic links are no less strong and the consequences are not less for both sides. It would have been easier for David Cameron if the referendum in Scotland did not take place, but this would have meant that the solution to a problem is simply being postponed. A problem that would only grow bigger. Now David Cameron has a threefold victory - he kept Scotland in, he taught a lesson in democracy to everyone in the EU and has a solid foundation for a future referendum on the EU. Now it is the Continent's turn to act.

Federica Mogherini | © Council of the EU

Federica Mogherini | © Council of the EU | © Council of the EU

| © Council of the EU Luis De Guindos | © Council of the EU

Luis De Guindos | © Council of the EU