Montenegro - the Great Reform Games Begin

Adelina Marini, January 8, 2014

After a decent oiling and a mild repair, the wheel of EU enlargement to the Western Balkans has again started turning and by the end of last year it seemed as if it had reached its full power. The rust has fallen after Serbia has finally been granted the long-awaited date for start of accession negotiations (end-January 2014) and Montenegro opened five crucial chapters, among which two key ones - 23 and 24 - related to justice, rule of law and fundamental rights. The movement was possible after the European Commission, under pressure by the member states, proposed a new approach to the Western Balkan countries which envisaged the opening of the toughest chapters, which are related to rule of law and a sustainable fight against corruption and organised crime, to happen in the very beginning of the negotiations process. These chapters will be closed among the last.

After a decent oiling and a mild repair, the wheel of EU enlargement to the Western Balkans has again started turning and by the end of last year it seemed as if it had reached its full power. The rust has fallen after Serbia has finally been granted the long-awaited date for start of accession negotiations (end-January 2014) and Montenegro opened five crucial chapters, among which two key ones - 23 and 24 - related to justice, rule of law and fundamental rights. The movement was possible after the European Commission, under pressure by the member states, proposed a new approach to the Western Balkan countries which envisaged the opening of the toughest chapters, which are related to rule of law and a sustainable fight against corruption and organised crime, to happen in the very beginning of the negotiations process. These chapters will be closed among the last.

And as the Western Balkan countries are the poorest in Europe, that is why their economic development will also be put under a spying glass and will be monitored closely and in detail by the European Commission. And that is the reason why the conclusions from the EU summit do not sound desperately impotent. Moreover, they radiate hope that the EU has finally started to feel the pulse of the problems in the region and is looking for a path toward their solution. The big question, however, is whether the countries from the region feel the wind of change and do they realise that from now on everything is in their hands. It is impossible to expect more political compromises as with previous enlargements and especially as with the case of Bulgaria and Romania, which were accepted in the EU practically completely unprepared.

This is written down quite clearly in the European Council conclusions from the end of December: "The Council welcomes that the new approach to negotiations on judiciary and fundamental rights and on justice, freedom and security, starting with Montenegro and building on the experience of previous accession negotiations, has put rule of law issues at the heart of the enlargement process. This is essential to ensure a solid track record in the fight against corruption and organised crime". In this sense, the Council expects the cooperation with Europol to continue in these areas as well as the closer cooperation with the member states and the European Commission's intention to enhance assessments and reporting before the Council on organised crime for each Western Balkan country on the basis of specific contribution from Europol.

Further on in the conclusions, it is underscored that the rule of law is the key for the economic development and the creation of a favourable business environment and investment climate. In this vein, the leaders of the 28 member states welcome the European Commission's proposal to enhance the dialogue on economic governance with the enlargement countries, of which euinside wrote in detail (and here).

The Montenegrin guinea pig

The tiny Balkan nation is the first the Commission will test its new approach on. What will be the progress of the country, known for its well developed organised crime and corruption, will be crucial for the success of the enlargement from now on, because, as I mentioned above, the EU will no longer make compromises with neither of the candidate countries. On December 18th there was a meeting of the association council between the EU and Montenegro, during which a decision was taken to open five new and fundamental for the reorientation of the negotiating process chapters. Those are: Chapter 5 (public procurement), 6 (company law), 20 (enterprises and industrial policy), 23 and 24. Chapter five has proved problematic for a country like Bulgaria and the perfection of the system for public procurement has been included in the monitoring under the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (CVM). However, to no avail.

As it becomes clear from the European Commission's annual progress reports, all Western Balkan countries have issues with company law which is a significant hurdle for their economic development. That is why, the opening of Chapter 6 and also of Chapter 20, together with the other three chapters, in the very beginning of the negotiations gives grounds to believe that the country will have sufficient time not only to adjust its legislation to the European acquis in those areas, but also to establish a tradition and sustainability. This means that the frequency of amendments to key legislation to serve the momentary political conjuncture will be reduced, which is also a bitter experience with Bulgaria and is also noted in the reports on the Western Balkans.

Commissioner Stefan Fule pointed out that the opening of precisely these chapters was a milestone in the negotiations process. "And I'd say that it's actually, indeed, a history in making", he said with a slight sense of celebration. Fule warned immediately afterwards, however, that in order to avoid this history to be endlessly long and to ensure it would be successful, the efforts of the entire Montenegrin society would be required, especially of the citizens'. To ensure implementation of the commitments of the Montenegrin government, the Commission for the first time is introducing interim benchmarks, the implementation of which will be monitored every six months. There are interim goals that will be very closely monitored. They will reflect the country's progress. And as all the questions of Montenegrin journalists were going round the question "what will happen if Montenegro failed", Mr Fule said there were interim check-points everywhere.

Besides, he said, all action plans as well as the interim reports on their implementation will be uploaded on the government's website to be viewed by Montenegrin citizens. Here the Commission obviously expects that the citizens will exert pressure on their politicians to stick to the commitments. This is not impossible against the background of the series of protests in the region precisely against corruption (Slovenia, Bulgaria and to some extent in Romania). The main message, though, is that the speed will be set by Montenegro. May be this is the reason why no one at the joint news conference after the end of the association council asked when Montenegro can be expected to become a member of the EU. Igor Luksic, former prime minister and now a minister of foreign and European affairs, said that the rule of law could not be achieved overnight. "Rule of law is not easy to achieve. It takes time", he said, but was confident that Montenegro could succeed.

The question is how

Stefan Fule underlined several times that the fight against corruption and organised crime was a priority. In this vein, Montenegro can choose from three paths. The easiest is the one Bulgaria is walking on. However, it goes in a circle and does not lead to results. Throughout the years Bulgaria has specialised in preparing action plans, reporting measures (usually a specific number: 50, 100, etc), in writing strategies, establishing state structures, merging them, in changing their leadership and, generally, in doing nothing. The outcome is visible - an economy on the edge of growth, with growing unemployment, especially among the young people, non-attractive for investors, instable legal environment, many months of protests, erosion of democracy and media environment. In Bulgaria, corruption, organised crime and conflict of interest are being handled at too many levels and therefore by no one.

The latest body - BORKOR, designed to prevent corruption - is practically teethless and has the main purpose simply to exist in the legal world. Recently, the leadership of the body has been changed, but its powers have not been increased. Bulgaria does not have even one high level politician convicted  of corruption, while all mafia killings in the past decades have remained unresolved. Conflict of interest has also failed and is a subject of political influence.

of corruption, while all mafia killings in the past decades have remained unresolved. Conflict of interest has also failed and is a subject of political influence.

The second path is that of Romania. Much harder than the Bulgarian one, but, still, not impossible. Bucharest has established an independent body to fight corruption, known as ANI (National Integrity Agency), the powers of which proved to be a thorn in the eyes of many Romanian politicians who tried several times to cut its wings. After furious reactions by the European Commission, the agency works, although not with the initial powers. But Romanian media regularly report on arrests of people, including ministers and MPs, suspected of corruption. Some of them have already been sentenced, but still this is the most difficult part - investigations to be brought to an end and to show a significant track record of sentences in Romania.

The most difficult path, but also most successful is that of Croatia. The EU's youngest member has at its disposal a very strong and obviously actively working body for the fight against corruption, organised crime and drugs trafficking. This is USKOK - the body to counteract corruption - which is part of the prosecution. The body consists of several departments which are responsible for its main activities. Those are: department for investigation and documentation; department for prevention of corruption and public relations; department of the state defenders who can also play the role of prosecutors; department of international cooperation and joint investigations; secretariat; accompanying services.

USKOK deals with misuse of office, disloyal competition, bribes, human trafficking, drugs trafficking, money laundering. Only two examples can give sufficiently clear perspective how does USKOK work and of the results. The star in Croatia's track record is Ivo Sanader, the former prime minister, who is serving a 10-year sentence on two cases and currently ongoing are more trials against him. In July last year, USKOK appealed against Sanader's sentence because it believed it is too small "given that vo Sanader is serving a sentence for deeds he perpetrated while holding high positions in the state". Instead of protecting the interests of the Republic of Croatia, he was led by his own interest, is the USKOK's argument to appeal to the regional court in Zagreb.

A much fresher example is the denouement of the Hippocrates affair. In the end of December, right between Christmas and New Year, USKOK indicted 364 doctors and a pharmaceutical company. All arrested are indicted on charges of taking bribes from the pharmaceutical company to prescribe its medicines. A huge scandal that has been taking place for more than a year, but USKOK managed to complete the investigation and send the indictment to the prosecution. Those are hundreds of volumes of charges. It is highly important to note that USKOK's investigation was triggered by a signal by Natasa Skaricic, an investigative journalist with the Slobodna Dalmacija newspaper. This is a very important detail because Montenegro has serious issues with the media environment where journalists are subjected to severe persecution.

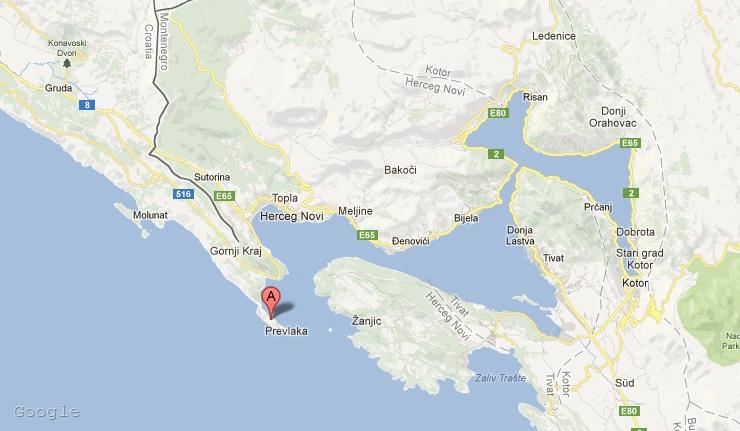

Right on the day when USKOK announced the indictment on Hippocrates, in the Montenegrin capital Podgorica a bomb exploded under the headquarters of one of the most circulated Montenegrin newspapers Vijesti. This is not the first attack against the newspaper's journalists or property. The EU delegation in Podgorica reacted sharply recalling that on December 18th Montenegro started negotiations on Chapter 23 which covers precisely the judiciary and the fundamental rights, including media and journalists' freedom. In this regard, the EU stated its firm expectation that the Montenegrin authorities will undertake the necessary actions to ensure freedom of media and expression. Freedom of media will allow them to be another source of correction and will make them another monitor of whether Montenegro is sticking to its commitments in the fight against corruption and organised crime.

Which path will Montenegro take?

At this stage it is too early to forecast what will the country decide. It is a fact that the action plans on the two key chapters (23 and 24) are on the government's website, although finding them proved to be hard. They are on the web page of the Directorate for counteraction of corruption DACI. This is the main body for prevention. However, a qualitative authority that would deal with "repression" of corruption, as it is put in the action plan for the period 2011-2014, is yet to be established. So far, the country has established several authorities. Those are the Administration for Anti-corruption Initiative, Administration for Prevention of Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorism, Directorate for Public Procurement, Commission for Control of Public Procurement Procedures, State Audit Institute, Commission for Prevention of Conflict of Interest.

At this stage it is too early to forecast what will the country decide. It is a fact that the action plans on the two key chapters (23 and 24) are on the government's website, although finding them proved to be hard. They are on the web page of the Directorate for counteraction of corruption DACI. This is the main body for prevention. However, a qualitative authority that would deal with "repression" of corruption, as it is put in the action plan for the period 2011-2014, is yet to be established. So far, the country has established several authorities. Those are the Administration for Anti-corruption Initiative, Administration for Prevention of Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorism, Directorate for Public Procurement, Commission for Control of Public Procurement Procedures, State Audit Institute, Commission for Prevention of Conflict of Interest.

Separately, special departments were established within the police, the prosecution and courts. It is envisageda specialised court to be established. Such an intention had the government of Boyko Borisov in Bulgaria, who interpreted in the wrong way the Commission's recommendation for a specialisation of judges to be able to investigate financial crimes. The achievements in the Montenegrin action plan show that the country is rather walking on Bulgaria's path - too many authorities, fragmented responsibility and in the end a lack of sentences on key cases. Probably this is the reason why the two questions of Montenegrin journalists on December 18th were aimed precisely at the availability of convictions - what will happen if in three year's time there are no sentences on key cases for high level corruption and what exactly is expected from these cases.

Among the measures envisaged in the plan that give hope that it is possible Montenegro to choose at least the Romanian path, are the creation of a special department of undercover investigators as well as of a special prosecutor's office to fight organised crime, corruption, terrorism and war crimes. The description in the action plan shows that something very similar to the Croatian USKOK is planned. The deadline for its establishment is November 2014.

There are two good news for Montenegro. One is that Croatia has provided its entire documentation from its accession in Croatian language which is completely understandable in Montenegro. Separately, the country established an excellency centre through which it distributes expertise and documentation to all countries in the region who ask for help. The other good news is that Montenegro can learn from Bulgaria's bad experience and avoid the mistakes the country made after its accession to the EU on January 1st 2007 and during the functioning of the CVM, which is till ongoing. The bad news is that Montenegro does not have the political chances Croatia and Bulgaria had. It will become a member of the EU only when it succeeds in convincing the EU that it is ready for membership. And that will not be easy.

Igor Luksic, Vesna Pusic | © Council of the EU

Igor Luksic, Vesna Pusic | © Council of the EU | © European Parliament

| © European Parliament | © Google

| © Google