The Fifth Element in the Autumn Economic Forecast

Adelina Marini, November 12, 2015

For years now demographics has been an important topic in the EU, provoked by an ageing population, but also by the migratory flows, internal for the EU until recently and from the outside in currently. The topic, however, remained at the level of national debate and measures. At the European level, apart from being mentioned in one context or another, demographics did not appear in European institutions’ analyses, nor was it present in supranational debates, let alone forecasts. All this despite the fact that, after the latest EU expansions, internal migratory flows caused considerable tension in the Union. And if internal migration has to some degree been stabilised, the migrant-refugee crisis has accelerated the change in the demographic picture considerably and thus its economic effect.

For years now demographics has been an important topic in the EU, provoked by an ageing population, but also by the migratory flows, internal for the EU until recently and from the outside in currently. The topic, however, remained at the level of national debate and measures. At the European level, apart from being mentioned in one context or another, demographics did not appear in European institutions’ analyses, nor was it present in supranational debates, let alone forecasts. All this despite the fact that, after the latest EU expansions, internal migratory flows caused considerable tension in the Union. And if internal migration has to some degree been stabilised, the migrant-refugee crisis has accelerated the change in the demographic picture considerably and thus its economic effect.

This is the reason behind the European Commission’s first attempt this year’s at analysing the effect of the demographic factor on EU economies in the short term. Moreover, the Commission is making the next step by placing the issue of the refugee crisis’ effect on the labour market and economy in general at a central spot in its autumn economic forecast. This being a debut, the Commission refers mainly to the existing international literature on the subject. The main message is that there is lack of data.

The demographic component of growth

The population in economically active age is expected to shrink by an average of 0.4% over the next four decades, according to Eurostat forecasts. This will have considerable effect on national budgets, mainly through the already overburdened pension and healthcare systems. According to International Monetary Fund assessments demographic changes in advanced economies could lower annual GDP per capita growth by half a percent by the year 2050. The comparison is based on the demographic structure in the year 2000. Per country analyses are far easier than the ones for a complex community like the European Union. According to the autumn economic forecast, the more economic integration grows, the more important does population mobility become, especially within the euro area. This conclusion should be taken into account when the future of the euro area is discussed (the five presidents’ report).

In this sense prime examples that illustrate this are Spain and Ireland, whose differences between pre-crisis and post-crisis levels of population growth show how important internal European labour force mobility is for dealing with asymmetric shocks. It is right here where the largest problems are. European labour market, although common in theory, is actually much less unified than the capital market for example, due to the existence of numerous barriers to labour force mobility. The most common barriers are discrepancies in qualifications, language barriers, recognition of diplomas, as well as restrictions in some member states. Mobility percentage, although growing over the last decade, remains too low. In 2002 just 1.5% of workers lived and worked in a member state different from the one they are born in. In 2014 this percentage is already 3.5%, reflecting the large expansion of 2004, which spawned the hysterics over the Polish plumber and the invasion of hungry Bulgarians and Romanians, but it is still too low in comparison to the one in the USA for example, where the percentage is double-digit.

In its autumn forecast the Commission makes an important clarification and it is that the portion of people living in EU member states without having EU citizenship is greater than the number of EU citizens living in another member state. This portion keeps growing over the last decade. According to the Commission, assessing demographic factors in member states must be a priority. This is even more necessary in the context of the refugee crisis.

Discrepancies in data

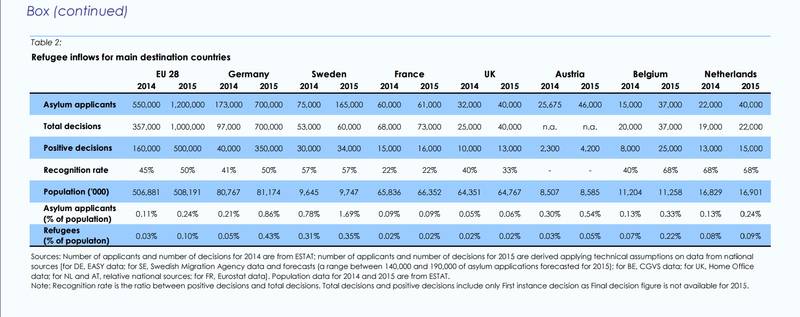

The EC is attempting to analyse the economic effect of the refugee influx, but it encounters a very serious problem there. Discrepancies in available data are considerable and reflect differences in definitions and coverage. Sometimes there is double counting of illegal migrants, filing asylum applications in several member states or inaccurate data because of unaccounted for illegal border crossings. Despite the efforts of Eurostat and different international institutions, as well as member states, available data is a source of uncertainty when we talk about assessing the macroeconomic effect of refugee flows. Not just economic effects, by the way, but social ones as well, for large numbers cause panic. Discrepancies of data is one of the most serious problems that had not been addressed at none of the numerous meetings of ministers and leaders in the Council on the refugee crisis issue.

According to the European border agency Frontex, over 710 thousand migrants have entered the EU in the first three quarters of 2015. By comparison, in 2014, 282 thousand people entered the EU. A huge part of them arrived in three countries – Greece, Hungary, and Italy. 350 000 people entered Greece alone, 204 000 entered Hungary, and 129 000 – Italy. We are talking about a diverse group of people, not all of whom are eligible for asylum. Out of all who have entered the EU from the start of 2014 up until now, over 1.2 million people have filed asylum applications. Again, we must keep it in mind, that there are discrepancies and duplicating of data.

The EC forecasts that the strength of the refugee flow will remain constant at the third quarter of 2015 level throughout 2016. In 2017 a gradual normalisation of flows is expected. Throughout the three-year forecast period it is expected that another three million people will enter the EU, which means a 0.4% increase of the population. This forecast accounts for some asylum applications being rejected. Rejection of applications is also a source of uncertainty regarding the forecast, because in some states the share of approved applications is considerably lower compared to others and this does not seem to be proportional to the number of applicants. Again we are talking about applying different criteria and definitions.

Because of too many inaccuracies and sources of uncertainty the EC states that at this stage it is impossible to assess the economic effect of refugees, but analysis is attempted based on existing literature with experience from other countries and other refugee crises. The economic effect is heavily dependent on the economic structure of member states and their workforce, on the characteristics of refugees (age and qualification), and on the capacity of the host country to integrate those, who gain refugee status. At the moment, there is a little more clarity regarding the effect of the refugee crisis on public spending. The most-affected transit states are expected to mark public spending growth of 0.2% of GDP this year, with stabilisation expected next year.

The rise of spending of destination states is expected to be similar, but an increase is forecasted for 2016. In Sweden, for example, which is among the countries with greatest share of refugees as a percentage of the population in the EU, public spending is expected to grow by almost 0.5% of GDP this year. The effect on economic growth, however, is expected to be lesser. According to the EC, economic migrants in general have the greatest positive effect, because with refugees the situation is quite different. According to studies, immigrants (from states outside the EU) receive far less social benefits than they contribute in the form of taxes or social contributions. Refugees are  far more inclined than labour migrants to work below their level of qualification (to some degree because of language troubles or non-recognition of qualifications).

far more inclined than labour migrants to work below their level of qualification (to some degree because of language troubles or non-recognition of qualifications).

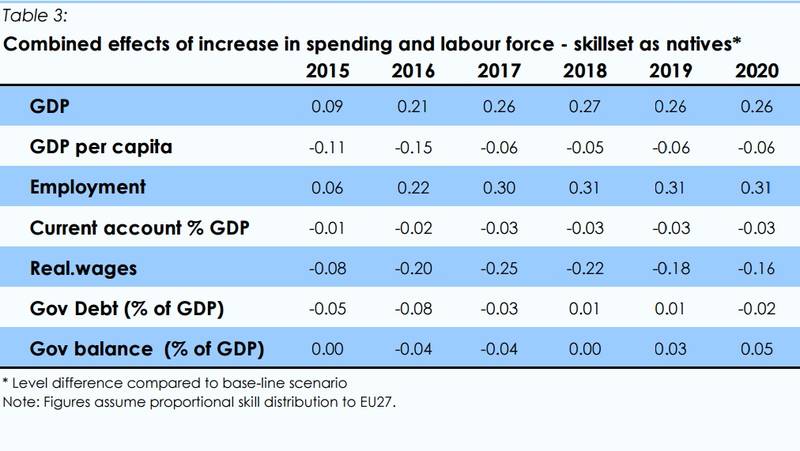

Based on technical simulations, the EC forecasts that labour force will increase by around 0.1% by the end of 2015 and by 0.3% in 2016 and 2017, provided the rate of approval of asylum applications is 50% and three quarters of the approved are in working age. The consequences of higher public spending and a larger workforce are expected to contribute to a small increase of GDP this year and next, up to around a quarter of a percent in 2017. Negative consequences to GDP per capita are expected to be negligible. If the increase of workforce is based on less qualified workers, the positive effect on growth will be further limited to 0.2% in the medium term.

At this stage, the surest consequences are to national budgets. Although the EC announced that it will give accurate analysis of the effect of refugees on public spending only after it announces the budget analyses of the member states in the euro area, few things are already visible in the autumn economic forecast. For Germany for instance, the EC points out that, regardless of refugees spending, the budget will continue to generate a surplus of 0.9% of GDP in 2015. By the end of the forecast period, however, (2017) refugees spending is expected to grow, but there is no exact data. The greatest part of spending will go for accommodation. Regardless, the German budget will remain at a surplus.

The Commission sees budget risks for the Netherlands as well, although exact figures are not available. Dutch budget is expected to mark a deficit of -1.1% this year, -1.4% next year, and -1.5% in 2017. Pressure on budget implementation is expected in Austria as well. Here, the Commission is more specific. Austrian budget is expected to absorb additional expenditure linked to the people looking for asylum in the realm of 0.5 billion euro, or 0.14% of GDP in this year. Risk, stemming from refugees, is projected for the Slovenian budget as well, but there are no calculations. Slovenian budget deficit gravitates around the 3% cap, but stays below it. This year, it is expected to be -2.7%. Slight improvement is expected in next year up to -2.5%, but for 2017 the forecast is for an increase to -2.9%. Slovenia has a large public debt as well – 84.2% of GDP for 2015. It is not clear, however, what the share of spending on refugees is as a percentage of the budget deficit. The EC expects the refugees will have an effect on Hungary’s budget as well.

The EC’s attempt to place demographic issues and the effect of the refugee crisis in the short-term horizon is doubtless a good idea, albeit a bit overdue. It is important that the EC insists that member states synchronise their data in order to remove inaccuracies, duplication, and definitions, so that the situation of the workforce in individual member states can be better assessed. This is also very important to the relocation scheme, negotiated in September, for it stipulates relocation is based on each nation’s need of workforce. It would also be interesting to see what the effect of refugees would be on unemployment levels. According to literature quoted in the  EC’s autumn forecast, refugees will have a positive effect on employment, but are unlikely to have a great influence on local citizens’ unemployment.

EC’s autumn forecast, refugees will have a positive effect on employment, but are unlikely to have a great influence on local citizens’ unemployment.

In any case, this depends largely on the refugees’ age, qualification, and whether the host country will allow them to enter the labour market. It also depends on the possibility of local population to find employment in another EU member state.

Translated by Stanimir Stoev

| © Council of the EU

| © Council of the EU Davutoglu, Tusk, Juncker | © Council of the EU

Davutoglu, Tusk, Juncker | © Council of the EU | © Vlada RS

| © Vlada RS